Sampson C. Bever: A Cedar Rapids Pioneer and His Contested Legacy

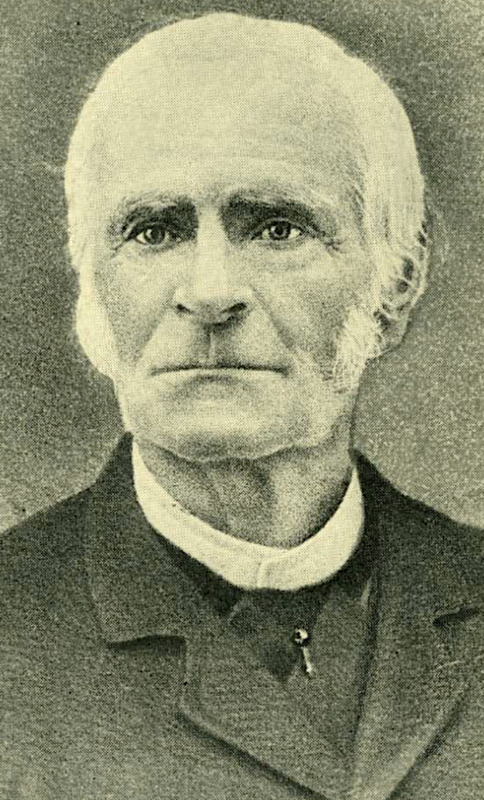

Sampson Cicero Bever (1808–1892), Cedar Rapids pioneer and banker

Sampson Cicero Bever (1808–1892) was a prominent early citizen of Cedar Rapids, Iowa – a wealthy banker, landowner, and civic benefactor whose name still echoes through local landmarks. Born in Ohio, Bever came to Cedar Rapids in the early 1850s with a small fortune and big ambitions. He helped establish the city's first bank and was instrumental in bringing the first railroad and hospital to town. By the end of his long life, Bever had amassed an estate worth hundreds of thousands of dollars and was regarded as one of Cedar Rapids' most influential financiers. His death in 1892, however, sparked a dramatic four-year legal battle among his children over his will – a battle that gripped the community with sensational courtroom scenes and ultimately reached the Iowa Supreme Court. This is the story of Sampson C. Bever's rise and the fierce fight over his legacy.

Early Life and Rise to Prominence

Bever was born in 1808 in Ohio and achieved success there as a young man, first in the glass manufacturing and mercantile trades. In 1851, at age 43, he ventured west with his wife Mary and their growing family, bringing an estimated $10,000 in gold (a considerable sum for the time) along with other property. The Bevers settled in the fledgling river town of Cedar Rapids, which would remain his home for the next four decades. Almost immediately, Sampson began investing in land – purchasing several farms in and around Linn County – and extending loans, laying the foundation of what would become a vast fortune in real estate and finance. One large tract southeast of town (over 500 acres known as the "Bever farm") was bought in the early 1850s for only a few thousand dollars; thanks to Cedar Rapids' rapid growth, that land would be worth over half a million dollars by the end of the century.

In addition to land speculation, Bever became a pioneer of local banking. Around 1860 he and his eldest son, James, opened S. C. Bever & Son, the first private banking house in Cedar Rapids. This venture proved so successful that in 1864 it was reorganized as the City National Bank, with Sampson Bever as a founding director and majority shareholder (he eventually owned three-quarters of the bank's stock). He remained deeply involved in banking until the early 1870s, when he began to scale back daily operations and let James take over as cashier and manager of the family's financial interests. The elder Bever's influence wasn't limited to banking, however. Often partnering with his friend Judge George Greene (another city father), he invested in critical infrastructure and civic projects. Notably, Bever helped finance and secure the first railroad into Cedar Rapids in 1859 and was involved in establishing St. Luke's Hospital, the city's first hospital. His business acumen was widely admired – one obituary praised his "exceptional if not extraordinary business sagacity," noting that "every enterprise that enlisted his attention and encouragement succeeded", and that he was "one of the most important…financial factors in the city" during his era.

By the 1880s, Sampson C. Bever was often described as a millionaire and counted among the richest men in Iowa. Much of his wealth was tied up in Cedar Rapids real estate (including downtown properties and those original farm tracts now on the edge of the growing city) and in the thriving City National Bank. He was also known for philanthropy and public spirit – beyond the hospital and other institutions he supported, Bever's family donated a wooded 70-acre parcel of his land to establish Bever Park in 1893, soon after his death, ensuring his name would live on in the city's landscape. By the time he died in the summer of 1892 at age 84, Bever left behind a legacy as one of Cedar Rapids' founding business leaders, as well as a sizable estate to be divided among his heirs.

The Contested Will and Family Rift

Sampson Bever's death on August 22, 1892 set the stage for a bitter family dispute over his fortune. He was preceded in death by his wife Mary (who died in 1885) and several of their children (three daughters had died young and a son, Henry, died in 1882). Five adult children survived him: Jane E. Bever Spangler, James L. Bever, George W. Bever, Ellen C. Bever Blake, and John B. Bever. In February 1886 – when he was about 78 years old – Sampson had executed a will (with a later codicil added in July 1891) outlining how his estate should be distributed. This will surprised many, because although Bever had often expressed in life that he wanted all his children to share his property more or less equally, the terms of the will were far from equal. Each of his two daughters was left a valuable home (built for them by their father) and a parcel of bank stock, but little else. By contemporary estimates, Jane and Ellen each stood to inherit around $40,000 worth of assets. The vast remainder of the estate – totaling roughly $650,000 in land, bank shares, railroad stock, and other investments – was to go to the three sons, with James slated to receive about $200,000 and George and John around $175,000 each. Small cash bequests and charitable gifts accounted for only a tiny portion of the will. In short, Sampson C. Bever's will heavily favored his sons' interests, especially those of James (who had been his right-hand man in business for years).

This lopsided division did not sit well with the Bever daughters. On September 27, 1892, weeks before the will was to be admitted to probate, Jane Spangler and Ellen Blake filed formal objections in Linn County District Court to contest their father's will. They alleged two key points: first, that Sampson Bever had not been of sound mind when making the will (and was mentally incapable of understanding his actions); and second, that the will and codicil had been procured through the fraud and undue influence of James L. Bever and George W. Bever – essentially accusing their brothers of manipulating an aging parent to skew the inheritance. Their aim was to have the will invalidated so that the estate would be divided according to law, which in Iowa meant all five children would share equally. The brothers, for their part, denied any wrongdoing and stood by the will's legitimacy. However, in an apparent tactical move, the will's proponents agreed to withdraw the 1891 codicil before trial and renounce any claim under that addendum. (The contents of the codicil were not fully publicized at the time, but it likely related to the creation of the Bever Land Company – a corporation the brothers had formed in 1891 to handle real estate development of the family farm land. By dropping the codicil, the brothers may have hoped to simplify the case and defend only the original will of 1886.)

With no settlement in sight between the siblings, the dispute headed to court. The Bever will case opened at the Linn County Courthouse in Cedar Rapids in January 1893, drawing intense public interest. Locals packed the courtroom's spectator benches each day to witness the prominent family's feud laid bare. It was evident from the start that any hope of an amicable resolution had evaporated – this would be a full-blown contest in open court. A who's-who of Iowa's legal community assembled on either side. The Bever sisters retained an accomplished team of attorneys led by Major William G. Thompson (a former congressman and respected trial lawyer) along with Charles B. "Charley" Keeler and others. The brothers and estate executors hired their own heavyweight counsel, including Colonel Charles A. Clark (a Civil War veteran and prominent Cedar Rapids attorney) and J. W. Jamison, among others.

Courtroom Drama: The Bever Will Trial of 1893

The trial that unfolded in January 1893 lasted over four weeks and became one of the most talked-about legal spectacles in Cedar Rapids history. Each side presented a very different portrait of Sampson C. Bever's final years. The sisters' case hinged on showing that their father had been in a state of mental decline – "senile dementia," as their lawyers termed it – such that he lacked testamentary capacity to make a valid will. In his opening statement for the contestants, attorney C. B. Keeler described how a person in Mr. Bever's condition could be easily influenced and might not fully comprehend his property or the natural objects of his bounty. Keeler outlined a timeline of Bever's alleged mental decline: after about 1875, the aging financier began to exhibit serious memory loss, poor judgment, and confusion. For example, he had been heard repeatedly lamenting his failing memory. He made uncharacteristic business decisions – renting out buildings to disreputable characters without realizing the consequences, something the once-shrewd Bever would never have done in his prime. More poignantly, family and friends would testify that Sampson became inattentive to major events around him: when his adult son Henry was dying of illness in 1882, Sampson reportedly failed to grasp the severity of the situation, expressing surprise at the death because "he did not think [Henry] was very bad". Likewise, when his wife Mary was gravely ill not long before her death, Sampson seemed unable to process her condition or care for her, necessitating constant help from others.

By the early 1880s, the contestants argued, Mr. Bever's mind was in clear decline. They described incidents such as a trip to California in 1879 during which Sampson became so forgetful and disoriented that it alarmed those traveling with him. In the mid-1880s, his daughters sometimes had to drive him to his own farm, only for him to not recognize the place until prompted. On one occasion around 1886, he visited that farm and, upon returning to his daughter's house, asked whose home he was in – seemingly not recognizing his own child's residence. Even around the very time the will was executed, witnesses recalled Sampson telling his grandchildren that "all his children were to share the property alike," a statement apparently at odds with the actual will he signed. All these "ludicrous mistakes," as Keeler put it, were more than simple forgetfulness – they were symptoms of a "gradual, slow death of the brain" that left Mr. Bever incapable of freely and rationally deciding how to dispose of a vast estate. In sum, the sisters aimed to prove their father had been a mentally feeble old man by 1886, vulnerable to suggestion and no longer fully in command of his faculties.

The brothers' defense, conversely, sought to uphold their father's competence and the integrity of the will. Their attorney Col. Clark vigorously denied that Sampson C. Bever was of unsound mind. While acknowledging the elderly man had some memory lapses, they argued he remained shrewd and capable in business matters well into the late 1880s. The real estate ventures and bank dealings during that period, they noted, still involved Sampson's guidance. Moreover, the defense pointed out that the will's dispositions were not irrational: the sons had worked closely in building the family wealth, while the married daughters had been provided for with homes and support during Sampson's life. It was natural, they argued, for a self-made patriarch to reward the sons continuing the business. There were also hints that the contest was fueled by greed and resentment, not genuine concern over mental state. As evidence mounted, the trial at times devolved into a duel of expert witnesses and acquaintances debating Mr. Bever's mental acuity. Local physicians testified about the signs of senility, and bank colleagues weighed in with their observations.

Given the high stakes and the prominence of those involved, the courtroom atmosphere was often intense – yet not without flashes of dry humor. One oft-retold anecdote involves a back-and-forth between the opposing lawyers during the trial. Colonel Clark, noting the fiery tenacity of the contestants' attorney Charley Keeler (who was short in stature with dark, almost impish features), quipped in exasperation, "If you would only put a feather in your hair, Charley, you'd make an ideal Mephistopheles!" The remark comparing Keeler to a devilish character from folklore drew chuckles from those present and showed even the defense could acknowledge the ferocity of the sisters' advocate. On another day, Major William G. Thompson – co-counsel for the Bever sisters – was urged by lead attorney Justice Hubbard to deliver a lengthy summation, at least two days long, to the jury. The veteran Thompson balked at the request, famously responding, "Great God, man, what shall I say to that jury except that here is the will, and there are the girls – they should have a part of this estate?" Thompson ultimately gave a forceful but succinct closing argument of only forty minutes (by far the shortest of his career for a jury trial), hammering home the basic fairness the daughters sought. As one reporter noted, his brevity and clarity made a strong impression – and indeed, when the case went to the jury, the verdict favored the contestants.

After hearing weeks of testimony and lawyer orations, the all-male jury returned its decision in February 1893. They found that the paper presented was not the valid will of Sampson C. Bever and voted to deny it probate. Notably, the jurors answered special interrogatories indicating they did not believe the will resulted from fraud or undue influence by the sons – essentially clearing the brothers of that accusation – but they did conclude that Mr. Bever lacked sufficient mental capacity on the date he signed the will. In effect, the verdict set the will aside on grounds of incapacity. The courtroom "erupted in murmurs" at the announcement; after such a protracted public fight, two of Cedar Rapids' grandest ladies had managed to defeat their brothers in court. The local press declared the outcome "a great victory for the Bever sisters," though it was also a sympathetic tragedy – the case had, as one account put it, "opened the grave of the dead banker" and laid bare family secrets in a way no one relished. Still, for Jane Spangler and Ellen Blake, it was a vindication: their father's estate would not be carved up strictly as the contested document dictated.

Appeal to the High Court

The battle was not over yet. James and George Bever, stunned by the jury's nullification of their father's will, immediately appealed the case to the Iowa Supreme Court. For the next two years, the Bever will case moved into the appellate courts, keeping the estate in limbo. During this period, land sales and development on the Bever properties were largely halted – for example, the Bever Land Company paused selling lots in the new "Bever Park Addition" because title to much of the land was tied up in the unresolved estate. The appeal reached the Iowa Supreme Court in Des Moines in late 1894. On January 29, 1895, the high court handed down its decision, which turned out to be the final word on the matter. The Supreme Court affirmed the verdict of the trial court, meaning the justices agreed that the evidence was sufficient to find Sampson Bever mentally incapable of making a valid will. The court's ruling methodically reviewed the conflicting testimony and concluded that it was not their role to second-guess the jury on such fact questions. Unless the verdict was plainly against the weight of evidence (which, in their view, it was not), the jury's determination on Mr. Bever's mental capacity must stand. Thus, the judgment remained: Sampson C. Bever's 1886 will was invalid, and he was deemed to have died intestate (without a valid will).

With the Supreme Court decision, the brothers' legal options were effectively exhausted. A further appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was theoretically possible but unlikely to succeed and extraordinarily costly. Rather than continue the fight, the five Bever siblings opted to reach a family settlement. In early 1896, an agreement was struck whereby all parties accepted an equal division of the estate – just as Jane and Ellen had originally wanted. The contested will was formally set aside, and the estate assets were apportioned in five equal shares among Jane, James, George, Ellen, and John. On January 20, 1896, local newspapers announced the Bever will case "Settled", noting that at long last the feud had ended amicably with a five-way split of the Bever fortune. Once the settlement was finalized by the court, the estate's executors (now effectively trustees for all the heirs) could finally proceed with converting assets to cash or distributing property. Almost immediately, business activity that had been on hold resumed – in March 1896, an advertisement ran in the Gazette inviting buyers for lots in the Bever Park Addition, cheerfully proclaiming those lots "are on the market again" now that the litigation was over.

The Bever will contest had lasted roughly three and a half years from Sampson's death to the settlement, and it left a lasting impression on Cedar Rapids. It was, as one retrospective later noted, "one of the most hotly contested cases in the county's history," not only because of the enormous property involved but also due to "the prominence of the parties" and the high-powered attorneys arrayed on each side. The case also highlighted the challenges of inheritance in an era when patriarchal norms often ran up against the rights of daughters in family property. In this instance, the Bever sisters prevailed in securing what they felt was their fair share, despite societal expectations that might have left them with far less. The legal drama concluded with a public compromise, but not before airing the private struggles of age, family loyalty, and greed that had played out behind the Bever mansion's doors.

Aftermath and Legacy

After the estate settled in 1896, Sampson C. Bever's fortune was divided equally, roughly one-fifth to each surviving child. Each heir suddenly had on the order of $130,000 in wealth (equivalent to many millions today) to manage. The resolution allowed the Bever family to move forward, and in the ensuing years each branch made its mark on Cedar Rapids in different ways:

• James L. Bever, the eldest son and longtime banker, continued in finance and real estate. He and his brother George reorganized their development interests as the Park Avenue Realty Company, the successor to the original Bever Land Co. This firm carried on with developing the family's former farmland in the city's southeast quadrant. James, who had several children of his own, remained a prominent figure in business until his death in 1916. His descendants stayed active in Cedar Rapids civic life. In fact, James's son James L. "Ren" Bever Jr. became an influential developer in the next generation: in 1923 Ren Bever's company built the landmark Bever Building on First Avenue, an elegant brick office block that signaled the eastward expansion of downtown. (The Bever Building still stood for nearly a century as a reminder of the family's presence.)

• George W. Bever, the second son, likewise invested his share in real estate ventures. He was known for his keen interest in urban planning – one contemporary credited "the energy, enterprise and taste of George W. Bever" for the attractive design of the Bever Park neighborhood. George never had children, but he poured his efforts into the development business and various community endeavors. Bever Avenue SE (a major thoroughfare to this day) was named for the family and runs through many of the areas they platted. George lived until 1928, witnessing the growth of Cedar Rapids into a small city that he helped shape.

• John B. Bever, the youngest son, was less public than his brothers, but he too benefited from the equal division. John had not been as deeply involved in the bank or land company prior to his father's death, so the settlement significantly boosted his fortunes. He and his wife did not have children, and John's later life was quieter; he died in 1916. Without direct heirs, some of John's estate eventually flowed back into community institutions and to his nieces and nephews.

• Jane Bever Spangler, the eldest daughter, had moved to California by the 1890s, but she returned to Iowa to fight for her inheritance. After prevailing, Jane went back west to Los Angeles, where she invested in property and lived comfortably on her share of the Bever wealth. She largely stayed out of the public eye thereafter. Jane died in 1913, and her only son did not remain in Iowa, so her line did not continue in Cedar Rapids. However, her determination in the will contest made her something of a local legend – a strong-willed woman who stood up for her rights.

• Ellen Bever Blake, the younger daughter, remained in Cedar Rapids and, in an interesting turn, became a real estate developer herself. Armed with capital from the settlement, Ellen partnered with a local realtor, Malcolm Bolton, to plat and promote new residential subdivisions in the early 1900s. In 1902 they opened Sampson Heights Addition (named in honor of her father), and a few years later Ellen helped develop the Grande Avenue Place Addition just north of Bever Park. One of the neighborhood's grand boulevards was even named Blake Boulevard after Ellen and her husband. This was a remarkable role for a woman of that era, and it showed how the contested inheritance ultimately enabled Ellen to carry on her father's legacy in city-building. Ellen Blake died in 1936, and her descendants remained part of the social fabric of Cedar Rapids.

Today, the imprint of Sampson C. Bever and his family is still evident around Cedar Rapids. Bever Park, donated from the family estate, continues to serve as a popular public park complete with a zoological garden (opened in the early 1900s) and leafy picnic grounds – a living memorial to the Bever name.

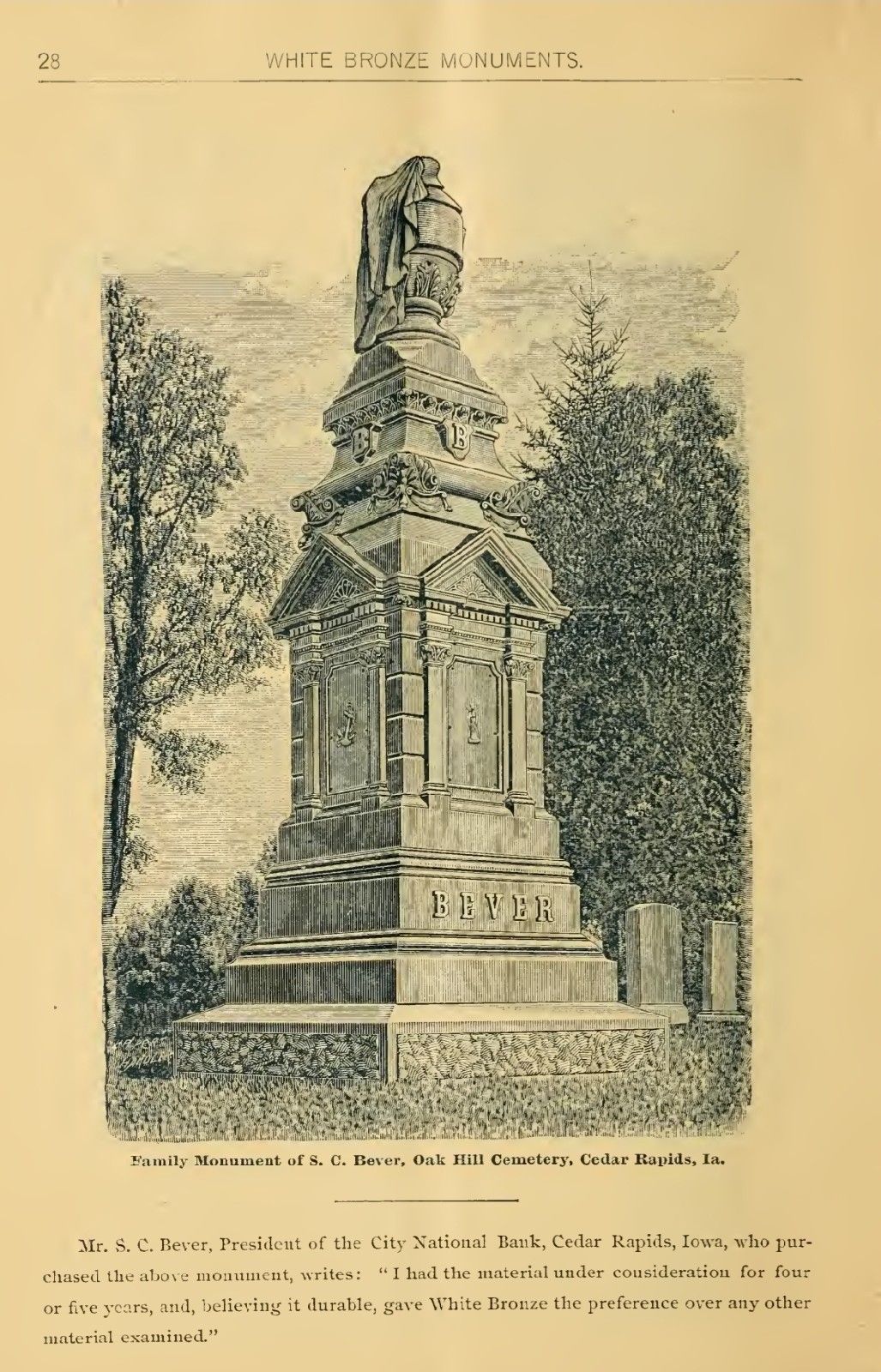

Bever Family Monument

The Bever Avenue and Blake Boulevard streets, the Bever Historic District in southeast Cedar Rapids, and structures like the old Bever Building all hark back to this pioneering family. The Bever children and grandchildren became builders, benefactors, and business people in their own right, but it was Sampson Cicero Bever's entrepreneurial spirit and wealth that set the stage. In the end, the fierce legal fight over his will ensured that each of his surviving children – sons and daughters alike – shared in that hard-earned fortune. The story of the Bever estate contest, with its courtroom clashes and ultimate compromise, has entered local lore as an example of how even in the Gilded Age of American prosperity, questions of family and fairness could ignite battles as dramatic as any fiction. It stands as a chapter in Cedar Rapids history that illuminates the city's early development, the human drama of inheritance, and the enduring legacy of one of its founding figures.

Sources

[1] Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, January 12, 1893

[2] Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, February 17, 1893

[3] Iowa Supreme Court (Bever v. Spangler), January 29, 1895

[4] Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, January 20, 1896

[5] Brewer, Luther A., and Barthinius L. Wick. History of Linn County, Iowa (Cedar Rapids: The Torch Press, 1911), pp. 479–480

[6] Redmond Park-Grande Avenue Historic District Nomination, National Register of Historic Places (2015), pp. 8–9

[7] Traci Rylands, "White Bronze Beauty: Lingering at Cedar Rapids' Oak Hill Cemetery, Part III," Adventures in Cemetery Hopping blog, Dec. 22, 2023